Bailes+Light director Benji Bailes uses light and creative technology to create an immersive underground experience with ‘Underfoot’.

Five summers ago, I first discovered the wonders of the Wood Wide Web. During our creative design period for Glastonbury Festival a colleague shared ‘From Tree to Shining Tree’, a Radiolab podcast which told the story of mycorrhizal networks: the connections between trees through underground fungal networks.

This was a fascinating story of collaborative biodiversity and symbiosis. It’s a story that would flit through my mind over the course of the next three years.

As an immersive lighting designer, I am often inspired to bring my passion to projects that communicate issues I care deeply about. I’ve used light and sound to encourage collaboration between humans and to campaign for the protection of nature.

As a member of the design team for Greenpeace at Glastonbury I’ve used lighting and creative technologies to involve audiences in important stories about human interaction with nature and was keen to develop these ideas and technologies further. A festival, however, isn’t a great environment to develop new technology. Water and electronics don’t tend to mix well. I needed a little time and space to develop these ideas and technologies further and to focus on them in the level of detail I would have liked.

Fast forward to 2020. With shows and festivals cancelled and the whole world staying at home, I finally had the time to think, play and dream. I wanted to experiment with the tools I have as a lighting designer to take people on a journey – and also give them the freedom to explore and discover an adventure of their own.

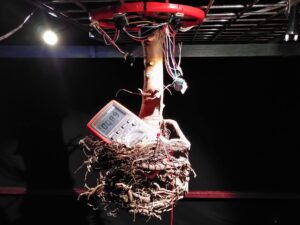

I got chatting with artist Poppy Flint, who asked me to help illuminate some tree roots for an exhibition. In this installation, participants would enter into an underground world – roots stretching out above their heads.

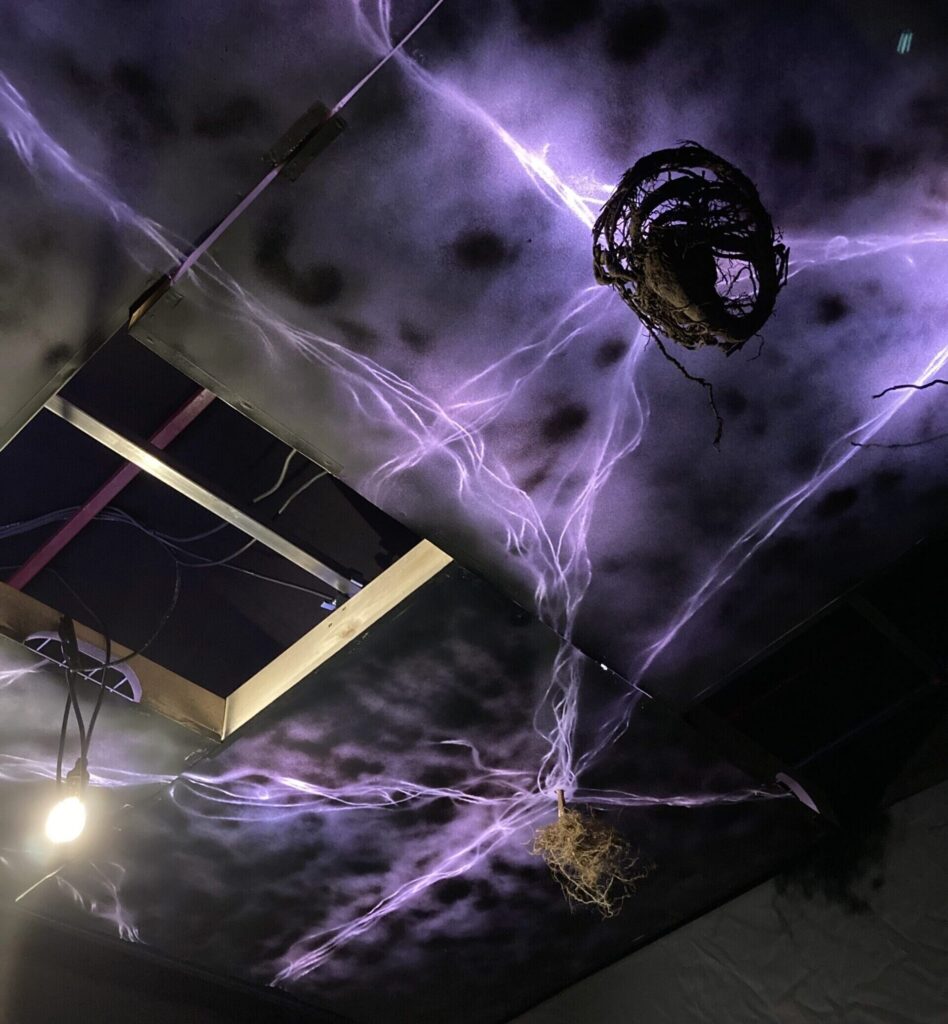

Poppy had a strong vision of leading people into a space that would move at a different pace to humans. She wanted to create an experience that would produce a sense of awe at the natural world, and simultaneously a sense of unease with our consumptive human relationship with the environment.

The story of the Wood Wide Web and mycorrhizal networks seemed like a perfect vehicle for the creative uses of technology I had been dreaming up. Could this be an opportunity to put some of my ideas into action? Poppy was game!

At the time, I had been playing with proximity sensors and contemplating how people interact with light and objects that are illuminated. In nature, plants communicate with each other and react to the proximity of friends or predators. How might we express these communications and reactions with light?

We felt that the mere existence of another life form – this time a human – in the underground domain would cause the roots to respond. I mocked up a root, sensor and light so it would get brighter as people approached it. We could expand on this first step and trigger other events such as sounds and atmospherics based on how close people came to the root.

Trials with individual sensors worked to some extent, but it was difficult to capture people’s movement over a large area. I had been using infrared (IR) motion sensors from above to achieve track movement, but within this low, ‘underground’ installation, there wouldn’t be enough space to capture reliable data. My colleague, Dan, suggested a different approach. We could plot a map and trace a person’s movement using two cameras

A bit of trigonometry and some coding, and voila! We could pinpoint the precise location of people in our installation, and their proximity to the roots and mycelium therein. This gave us the opportunity to develop a story that responded to people’s exploratory movements.

The human could now be the protagonist of the entire piece.

Illuminating the intricate beauty of the roots themselves was also an important part of the installation. By playing with depth and shadow I could make the hairs of the plant glisten and the hairs of the audience stand on end.

Plants help each other thrive by sharing nutrients. They can warn each other of threats such as insect predators. The mycelium of mycorrhizal fungi (the webs of fungi underground) pass on these messages and compounds, weaving their tendrils within, between and around plants and exchanging nutrients for their own survival and growth.

In our installation, I wanted to represent mycelium and the sharing of nutrients and signals with light. I’ve always struggled with the idea of light for light’s sake. I like light to enhance settings, sculptures or objects, not dominate them.

By representing these signals, light became an integral part of the narrative, rather than a separate element used to enhance the space.

Illuminating the intricate beauty of the roots themselves was also an important part of the installation. By playing with depth and shadow I could make the hairs of the plant glisten and the hairs of the audience stand on end.

Sound would also be an integral part of this underground journey. We worked with friend and sound designer, Lex Kosanke, who was keen to get involved. Lex helped us make sound a fundamental element of the narrative by giving each root a unique sound identity.

The result was ‘Underfoot’ (formerly ‘woven // dissonance’), an interactive audio-visual journey beneath the forest where participants create their own journey to explore their connection to nature.

Here in 2022 it still feels like I am part way through this underground adventure. We still have so much to learn and share, more stories to tell and people to inspire. I don’t yet know how this project will develop, but being able to encourage others to learn about and celebrate biodiversity and symbiosis drives me forward. I hope that we can build on our installation to create a fully interactive audio-visual experience that inspires many more people to respect and treasure our natural world.

You can watch a video made of the installation below.